The politics of industrialization

A central component of a successful development project is a well-thought out political strategy. In many low-income countries, political circumstances are unconducive to providing the support and inducement mechanisms necessary for firms to improve their productive capabilities. It is the task of developmentally-oriented leader to change this situation.

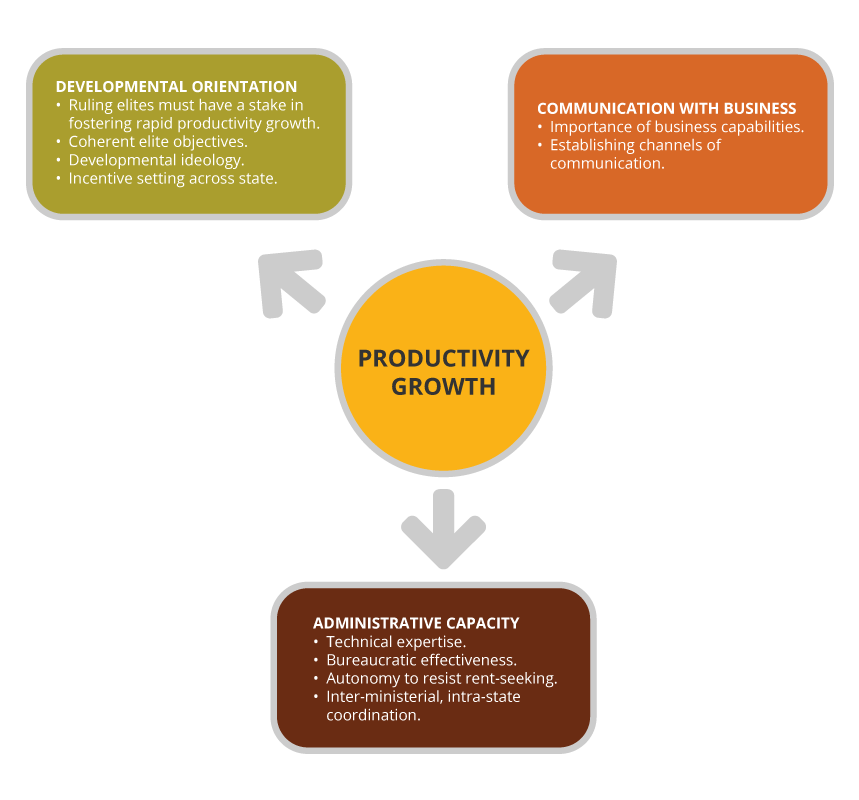

The success of industrial depends on the interactions between three types of organizations: firms, public bureaucracies, and political organizations. The relative organizational strength across each domain, and the relationships between these organizations, determine the most suitable strategy for a given political context.

From the point of view of a developmentally-oriented leadership, the central problem of a political strategy for industrial development consists of:[1]

A sequence of decisions over time on how to allocate political resources to (a) reconfigure political economy incentives and (b) strengthen organizations as means of improving firms’ capabilities, subject to political opposition and coalitional demands.

Incentives for investment and learning are an essential part of industrial policy, but without the strengthening of the bureaucratic and political organizations tasked with directing their implementation, they are unlikely to lead to a sustainable path to industrialization. However, improving state capabilities is a time-consuming process, partly based on the history, values and norms that underlie the quality of state structures, and it requires a long period of sustained political support.

The choice of strategy must be compatible with current administrative capabilities and political resources. Leaders should beware of pursuing strategies that are incompatible with these factors, since they could lead to the deterioration of whatever capabilities do exist.

Below we give some examples of ‘ideal types’ of states that can currently be found in Africa.

Hyenas

Failing states with high conflict and instability

Tigerfish

Predatory states, designed to extract and plunder from people and the economy

Hippos

Neo-patrimonial states, with clientelist arrangements where the state is used to pay off clients or appoint them into jobs

Lions

Nationalist, state-building projects, but still with very imperfect state capability

Development strategies will differ according to the limitations posed by the political economy. For instance:

-

In Hyenas and Tigerfish, the challenge is to forge coalitions and build institutions that can reduce violence and predation, while opportunities of engaging in industrial policy might be limited.

-

Hippos have limited scope for ambitious organizational strengthening, but adequate alignments of incentives can help improve industrial performance.

-

In Lions, the presence of strong political organizations may enable more ambitious strategies combining incentive restructuring and support to improve state capabilities.

These political strategies are inherently context-dependent, and locally-embedded leaders are best placed for navigating the political context. Great political skill is needed to forge an environment that is conducive to industrialization. This can involve the use of institutional prerogatives, working to generate consensus, shrewd political bargaining, and the capacity to inspire and mobilize the population, to name a few.

Reforming the State

How do you change the rules of the game? Of course, there is no answer to this question that can be unconditionally applied everywhere, but one common strategy consists of carving up parts of the state to take care of a regime’s patronage needs, while setting up streamlined, professional ministries to in charge of economic policy and reporting directly to the head of state.

In an authoritarian setting, we have the example of Park Chung-Hee’s South Korea (1961-1979). After coming to power through a military coup, he expanded the bureaucracy, instituting a ‘bifurcated’ system[1] whereby certain ministries served political functions, while others were responsible for technical decisions on the economy. Among the latter were the Economic Planning Board (EPB), the Ministry of Trade and Industry, and an economic secretariat operating from the presidential residence[2].

But state reform is not only possible in authoritarian settings. Barbara Geddes[3] discusses the efforts of Brazilian political leaders to reform the state since the 1930’s. At times, these leaders were highly successful, even under democracy, and the country was the first in Latin America to institute a meritocratic civil service. Geddes lists conditions that contribute to the creation of more effective states:

- Insulation of agencies responsible for economic development from the clientelist pressures of politics.

- A political environment where it is in the chief executive’s interest to implement programmatic policies, often against the opposition of the legislature, and a well-functioning bureaucracy will help him in this task.

- An executive well-endowed with political and financial resources.

However, a key challenge in democratic regimes is to ensure that even when there is a change in government, the competence of agencies established by the previous government does not get eroded to buy political support.

[1] David C. Kang (2002) – Crony Capitalism: Corruption and Development in South Korea and the Philippines, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

[2] Atul Kohli (2004) – State-Directed Development: Political Power and Industrialization in the Global Periphery, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

[3] Barbara Geddes (1990) – “Building State Autonomy in Brazil, 1930-1964”, Comparative Politics, 22(2): 217-235

Leaders should be able to simultaneously manage opposing interests and coalitional demands, while implementing technically-sound policies. Common strategies used in the past for this purpose include the ring-fencing of priority policy fields, or introducing economic policies that credibly commit the government to pursuing a certain course of action. In parallel, these leaders responded to political imperatives in less important policy areas, or in ways designed to minimize the negative impact on economic performance.

[1] For an in-depth discussion of the reasoning behind this formulation and a review of the literature on the political economy of industrial policy, see Nicolas Lippolis and Stephen Peel (2018) – “Political Strategies for Industrial Development”. Background Paper for Programme on Rethinking African Paths to industrial Development. Oxford: Blavatnik School of Government and Centre for the Study of African Economies, University of Oxford.